Categories

Lifestyle Modification as a Means to Prevent and Treat High Blood Pressure

Author Affiliations

- Professor of Medicine, Epidemiology, and International Health (Human Nutrition), Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology and Clinical Research, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore, Maryland.

- Correspondence to Dr. Lawrence J. Appel, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, 2024 East Monument Street, Suite 2-645, Baltimore, MD 21205-2223. Phone: 410-955-4156; Fax: 410-955-0476;

Abstract

ABSTRACT. High blood pressure (BP) is one of the most important and common risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and renal disease. The contemporary approach to the epidemic of elevated BP and its complications involves pharmacologic treatment of hypertensive individuals and “lifestyle modification,” which is beneficial for both nonhypertensive and hypertensive persons. A substantial body of evidence strongly supports the concept that lifestyle modification can have powerful effects on BP. Increased physical activity, a reduced salt intake, weight loss, moderation of alcohol intake, increased potassium intake, and an overall healthy dietary pattern, termed the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, effectively lower BP. The DASH diet emphasizes fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products and is reduced in fat and cholesterol. Other dietary factors, such as a greater intake of protein or monounsaturated fatty acids, may also reduce BP but available evidence is inconsistent. The current challenge to health care providers, researchers, government officials, and the general public is developing and implementing effective clinical and public health strategies that lead to sustained lifestyle modification. E-mail: lappel@jhmi.eduThis e-mail address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Efforts to control the epidemic of high BP and its cardiovascular and renal complications have traditionally focused on pharmacologic treatment of persons with established hypertension. Such efforts reflect an impressive body of evidence that has documented the beneficial effects of antihypertensive drug therapy in preventing BP-related clinical complications. Still, reliance on drug therapy alone is an incomplete solution to the epidemic of high BP and its complications. First, it is well recognized that the risk of BP-related cardiovascular and renal disease increases progressively throughout the range of BP, including ranges of BP previously considered normal. Furthermore, a large fraction of adults have a BP that is above optimal and yet is below the traditional threshold for drug treatment. Such BP levels nonetheless place individuals at increased risk of BP-related complications, yet they are not candidates for drug therapy. In view of these considerations, national and international policy-making bodies recommend lifestyle modification as a means to prevent and treat hypertension and thereby prevent cardiovascular and renal disease in the whole population.

Role of Lifestyle Modification

Lifestyle modification, previously termed nonpharmacologic therapy, has important roles in hypertensive as well as nonhypertensive individuals. In hypertensive individuals, lifestyle modifications can serve as initial treatment before the start of drug therapy and as an adjunct to medication in persons already on drug therapy. In hypertensive individuals with medication-controlled BP, these therapies can facilitate drug step-down and drug withdrawal in highly motivated individuals who achieve and sustain lifestyle changes. In nonhypertensives, lifestyle modifications have the potential to prevent hypertension, and more broadly to reduce BP and thereby lower the risk of BP-related clinical complications in whole populations. Indeed, even an apparently small reduction in BP, if applied to an entire population, could have an enormous beneficial effect on cardiovascular events. For instance, a 3-mmHg reduction in systolic BP should lead to an 8% reduction in stroke mortality and a 5% reduction in mortality from coronary heart disease.

The following sections highlight the effects of specific lifestyle therapies that reduce BP.

Increasing Physical Activity.

An increased level of physical activity can lower BP, independent of concomitant changes in weight. A recent meta-analysis of 27 randomized trials documented a 4 mmHg net reduction in systolic BP among individuals assigned to an aerobic exercise intervention. Interestingly, the magnitude of BP change appeared to be independent of the exercise intensity. In addition to a direct beneficial effect on BP, increased physical activity should also lower BP by facilitating initial weight loss and by promoting maintenance of weight loss, once achieved. In aggregate, these findings support the recommendation of the US Surgeon General that persons exercise 30 min or more most, if not all, days of the week.

Reducing Salt (Sodium Chloride) Intake.

A high intake of salt (sodium chloride) adversely affects BP. Evidence includes results from animal studies, epidemiologic studies, and clinical trials. Recent studies have documented that a reduced sodium intake can prevent hypertension (TOHP2, phase 2 of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention), can facilitate hypertension control in older-aged persons on medication (TONE, Trials of Non-Pharmacologic Interventions in the Elderly), and can potentially prevent cardiovascular events in overweight individuals. TOPH2 documented that sodium reduction, alone or combined with weight loss, can reduce the incidence of hypertension by approximately 20%. In the TONE, a reduced salt intake with or without weight loss effectively reduced BP and the need for antihypertensive medication in older persons. In both trials, the dietary interventions reduced total sodium intake to approximately 100 mmol/d. Such data reinforce current guidelines to limit salt intake to 6 g/d, the equivalent of 100 mmol of sodium (2400 mg) per day.

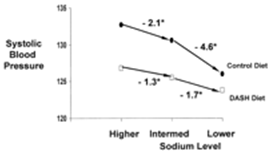

Results from the recently completed the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-Sodium feeding study have documented that an even lower intake of sodium, approximately 60 mmol/d, further reduces BP in a broad population of nonhypertensive and hypertensive individuals. The DASH-Sodium trial tested the effects on BP of three levels of sodium reduction in two distinct diets. The three sodium levels were “higher” (target of approximately 143 mmol/d, reflecting typical US consumption), “intermediate” (target of 106 mmol/d, reflecting the upper limit of current US recommendations), and “lower” (target of 65 mmol/d, reflecting a level that could produce additional lowering of BP). Main results are displayed in Figure 1. In a typical American (control) diet, reducing sodium intake from the higher to the intermediate level significantly reduced systolic BP by 2.1 mmHg; reducing sodium intake from the intermediate to the lower level further reduced systolic BP by 4.6 mmHg. In the DASH diet, corresponding changes in systolic BP were −1.3 and −1.7 mmHg, respectively. The effects of sodium reduction tended to be greater in blacks than whites. Compared with the control diet with higher sodium, the DASH diet with lower sodium reduced systolic BP by 7.1 mmHg in nonhypertensive persons, and 11.5 mmHg in hypertensives. The pattern of results was similar for diastolic BP.

Figure 1.

Effects of reduced sodium intake in a typical American (control) diet and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet: Main results from the DASH-sodium trial.

Results from the DASH-Sodium trial support current, population-wide recommendations to lower salt intake. These data also document the benefit of consuming the DASH diet (discussed below) and reducing salt intake. To reduce salt intake, consumers should choose foods low in salt and limit the amount of salt added to food. However, even motivated individuals find it difficult to reduce salt intake because of the huge amount of salt added by food manufacturers during food processing. Hence, any meaningful strategy to reduce salt intake must involve the efforts of food manufacturers who should reduce the amount of salt added during preparation.

Maintaining a Healthy Body Weight.

A consistent body of evidence from observational studies and clinical trials indicates that weight is positively associated with BP and hypertension. The importance of this relationship is reinforced by the high and increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity throughout the world. Virtually every clinical trial that has examined the influence of weight loss on BP has documented that weight reduction lowers BP. Interestingly, reductions in BP occur before (and without) attainment of desirable body weight. In one study that aggregated results across 11 weight loss trials, average systolic and diastolic BP reductions were 1.6/1.1 mmHg per kilogram of weight loss. Lifestyle intervention trials have uniformly achieved short-term weight loss. In several instances, substantial weight loss has also been sustained over 3 yr or more.

Moderating Alcohol Intake (among Those Who Drink).

The relationship between high alcohol intake (typically three or more drinks per day) and elevated BP has been documented in many epidemiologic studies. Trials have also reported that reductions in alcohol intake can lower BP in normotensive and hypertensive men who are heavy drinkers. In the Prevention and Treatment of Hypertension Study, which studied moderate-to-heavy drinkers, a reduction in alcohol intake lowered BP to a small, nonsignificant extent. In aggregate, available evidence supports a recommendation to limit alcohol intake to no more than two drinks per day (men) and one drink per day (women) among those who drink.

Increasing Potassium Intake.

In contrast to the direct relationship of salt intake with BP, high levels of potassium are associated with low BP. Although observational data have been reasonably consistent, data from individual clinical trials have been less consistent and persuasive. However, a meta-analysis of these trials documented that supplementation of diet with potassium lowered BP. On average, a typical dose of 60 to 120 mmol/d of supplemental potassium reduced systolic and diastolic BP by 4.4 and 2.5 mmHg in hypertensives and by 1.8 and 1.0 mmHg in normotensives. This study also documented greater BP reductions from potassium in blacks compared with whites and greater BP reduction from potassium at higher levels of salt intake. Because a high dietary intake of potassium can be achieved through diet rather than pills and because potassium derived from foods also comes with a variety of other nutrients, the preferred strategy to increase potassium intake is to consume foods rich in potassium rather than supplements.

Consuming a Diet That Emphasizes Fruits, Vegetables, and Low-Fat Dairy Products, and That Is Reduced in Fat and Cholesterol.

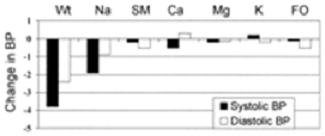

Certain dietary patterns have been associated with low BP. For instance, in observational studies and two clinical trials, vegetarian diets have been associated with lower BP. The nutrients responsible for the BP-lowering effects of these diets have remained uncertain. Attention has focused on macronutrients (particularly the type and amount of fat), micronutrients (potassium, magnesium, and calcium) and fiber. However, data from observational studies and small scale trials have been extremely inconsistent. Phase 1 of TOPH tested the individual effects of these micronutrients and lifestyle factors on BP. In this large scale trial that enrolled over 2000 persons with high normal diastolic BP (80 to 89 mmHg), calcium and magnesium had no significant effect on BP, whereas weight loss and sodium reduction each lowered BP (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Effects on BP at 6 mo from weight loss (Wt), sodium reduction (Na), and stress management (SM) interventions, and pill supplementation with calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), potassium (K), and fish oil (FO): Main results from phase 1 of the trials of hypertension prevention (TOHP1).

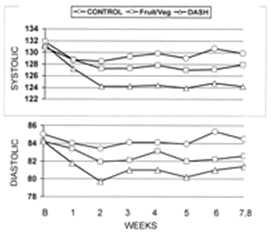

In view of these perplexing and inconsistent data, the DASH trial was a controlled feeding study designed to test the effects of modifying whole diets on BP. Main results are displayed in Figure 3. The most effective diet, now termed the DASH diet, emphasizes fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products; includes whole grains, poultry, fish, and nuts; and is reduced in fat, red meat, sweets, and sugar-containing beverages. The diet is rich in potassium, magnesium, and calcium. Among nonhypertensive individuals, this diet reduced systolic and diastolic BP by 3.5 and 2.1 mmHg, respectively. In hypertensives, corresponding BP reductions were striking, i.e., 11.4 and 5.5 mmHg. Similar to the meta-analysis of potassium, the DASH diet reduced BP to a greater extent in African Americans than non-African Americans.

Figure 3.

Mean blood pressure by week of feeding in a typical American diet (control diet), a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, and the DASH diet (rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products and reduced in saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol): Main results of the DASH trial.

Other Factors That Might Influence BP.

Evidence from observational epidemiologic studies and several small trials suggest that supplementation of diet with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (omega-3 PUFA, commonly termed “fish oil”) can reduce BP. In two meta-analyses, high doses of omega-3 PUFA, typically 3 g or more of fish oil per day, reduced BP. Significant BP reductions were evident in hypertensive individuals but not in nonhypertensive persons. However, the high dose of omega-3 PUFA with its attendant side effects precludes recommendations for its routine use as a means to lower BP.

The effects of monounsaturated fatty acids on BP have received scant attention. In one recent trial, a diet rich in monunsaturated fatty acids lowered systolic and diastolic BP by 8 and 6 mmHg, respectively. In view of these results, as well as the enormous interest in “Mediterranean” style diets that are associated with reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, additional research on the BP effects of monounsaturated fatty acids is warranted.

Epidemiological studies strongly support the hypothesis that increased protein intake can lower BP. This inverse relationship has been documented in several populations, including Japanese rural farmers, Japanese-American men in Hawaii, American men in two cohort studies, British men and women, Chinese men and women, and American children. The source of protein, animal versus nonanimal, may also have a differential effect on BP. To date, only small, underpowered trials have tested the effect of protein, amount or type, on BP.

Discussion

Multiple dietary factors influence BP. The effects of each factor are typically modest, particularly in normotensives, yet the combined effects can be substantial. Hence, public health and clinical recommendations should remain multifaceted. A related theme is that it is exceedingly unlikely that a “magic nutrient” will be found. Even the impressive reductions reported in the DASH study are best interpreted as a combined effect from multiple dietary factors rather than the effects of a single factor.

Hypertensive individuals, older-aged persons, and blacks are groups that are especially sensitive to the effects of diet on BP. The greater efficacy of lifestyle modification in hypertensives compared with nonhypertensives is a ubiquitous finding. In the DASH-Sodium feeding study, persons >45 yr achieved significantly greater BP reductions from the DASH diet with reduced salt intake than younger individuals (17). The TONE trial, which enrolled individuals 60 to 80 yr of age with medication-treated high BP, documented that older-aged persons can achieve and sustain reductions in sodium and weight and that these lifestyle changes lower BP and the need for antihypertensive medication (4). Likewise, evidence from clinical trials has documented that a reduced salt intake, increased potassium intake, and the DASH diet are particularly effective in blacks. Given the substantial burden of vascular disease in hypertensives, older-aged persons, and blacks, targeted public health efforts that promote lifestyle modifications in these populations are warranted and, if adequately implemented, should be especially effective.

Summary

Multiple dietary factors influence BP. Although each factor typically has a modest effect, the combined effects can be substantial. From a public health perspective, even a small reduction in BP should have a tremendous, beneficial effect on the occurrence of hypertension and its complications. In view of the current epidemic of BP-related diseases and the proven effects of lifestyle modifications on BP, the current challenge to health care providers, researchers, and public officials is to develop and implement effective clinical and public health strategies that achieve and maintain healthy lifestyle modification.

© 2003 American Society of Nephrology